Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi is a name to conjure with. In the index of historical prominence as calculated by the website Pantheon, he is up there among the great and the good, the prominent and the evil politicians. He rubs shoulders with some strange political personalities, all born in his lifetime. King Farouk of Egypt, Hassan II of Morocco, Justin Trudeau of Canada, and Clara Petacci, Mussolini’s last mistress, all have an HPI or ‘historical personality index’ over 70, indicating several hundred thousand visits to their biographical entries in a multitude of languages on Wikipedia every year. If you narrow the search to those political figures who died in Austria, he ranks alongside Simon Wiesenthal and Kurt Waldheim. And his star is rising. Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi (RCK) registered at 158 on the overall political ratings in 2020, up 427 places in one year in the Pantheon charts. It reflects a dramatic rise of interest in the man who first made the peaceful unification of Europe a political program.

Born in 1894 in Tokyo, RCK was the second son of an Austro-Hungarian diplomat and his Japanese consort. They married the following year to legitimise their offspring and secure an inheritance in Bohemia, bringing their family back to Ronsperg in the Sudetenland, now Pobezovice in the Czech Republic. Richard later described his idyllic childhood there in the family castle as ‘paradise’. It was only disturbed by the premature death of his father in 1906 and the adolescent Richard’s subsequent education at Vienna’s Theresianum, the elite boarding school of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

RCK, however, was already thinking in terms of continents, not countries.

Between school and university in 1913 this handsome and intelligent young aristocrat fell in love with the leading lady of the Viennese stage, Ida Roland. To the horror of his conservative, catholic family, he lived openly with this half-Jewish, half-Slovak star, twelve years older than him, already divorced and with a five-year-old daughter. Their eclectic circle embraced artists and thinkers, writers and politicians who had outgrown the stifling conservatism of the old Empire. Ida clearly opened Richard’s eyes and mind to a wider world emotionally, socially and intellectually.

Both of them were pacifists during the First World War. In the spirit of national self-determination, the victorious allies at the Paris Peace Conference created new states across Central and Eastern Europe, which immediately went to war with each other over the new borders and issues of minorities. RCK, however, was already thinking in terms of continents, not countries. He envisaged a Europe-wide alliance that would submit the multiple new border claims to a continental court, whose decisions would be accepted without any recourse to arms. That was what the impotent League of Nations was meant to provide but, as Mussolini succinctly put it, the League could be “useful when the sparrows twitter”, but was “useless when the eagles scream.” More was clearly needed, and RCK decided to provide it.

The Versailles settlement made RCK and Ida citizens of Czechoslovakia and he took his plan to Thomas Garigue Masaryk, the new President. He was sympathetic to the young man’s goals and introduced him to his Foreign Minister, Edvard Benes, who gave Richard and Ida Czechoslovak diplomatic passports to help them further their goals in Vienna.

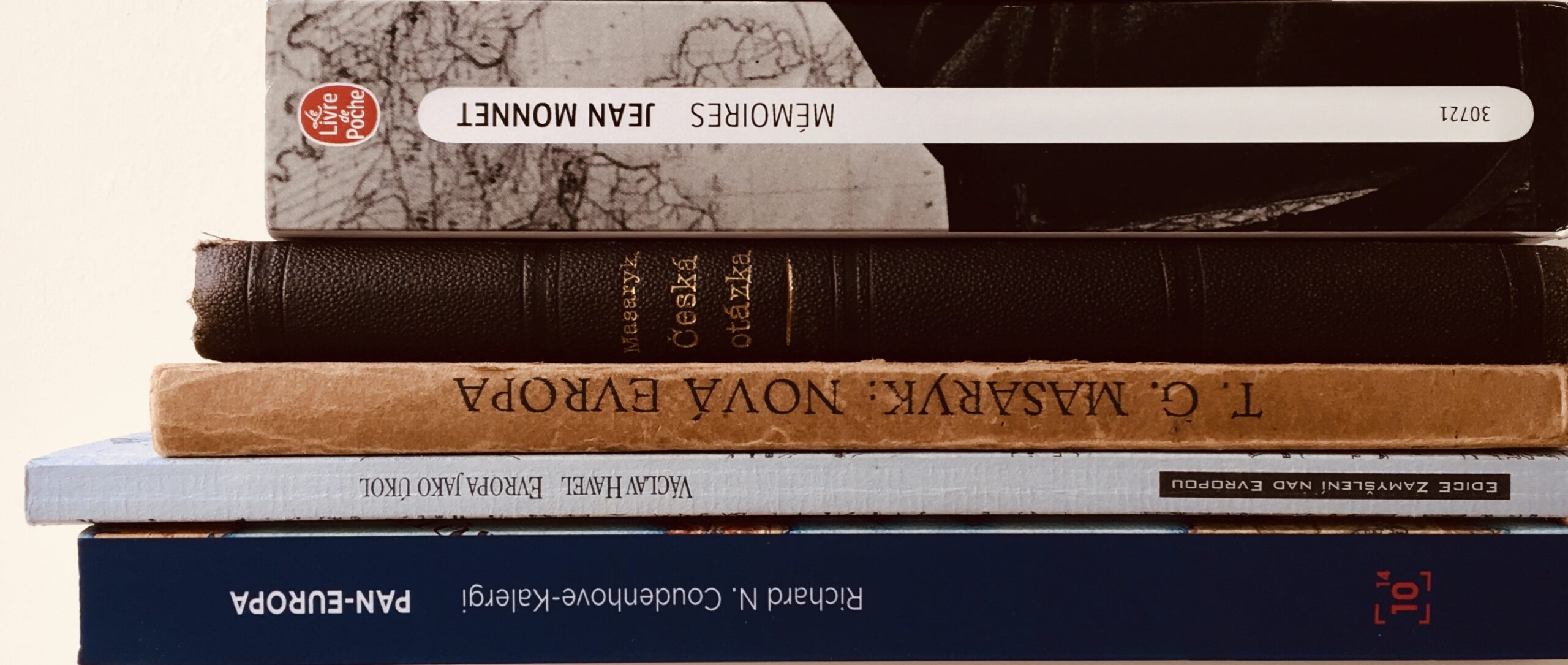

It was here in October 1923 that RCK published PanEuropa, his bestselling political manifesto, and set up the PanEuropa Union. It quickly became a wildly successful movement with thousands of followers across the continent, drawn essentially from the liberal intelligentsia, including Freud, Einstein and both Thomas and Heinrich Mann. They held Congresses in Vienna, Berlin and Basel that attracted thousands of supporters as well as international press coverage. Wags in Vienna suggested RCK and Ida wanted to be President and First Lady not just of their political movement but of the United States of Europe they were working for as well.

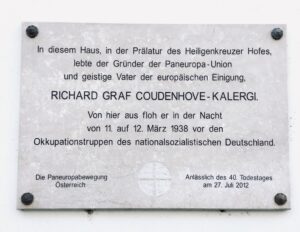

They moved into the Benedictine abbot’s apartment in the Heiligenkreuzerhof, recently vacated as the incumbent found it more convenient to lodge in the abbey outside the city and motor in for any political appointments. This magnificent residence became their Viennese home and the ‘embassy’ of PanEuropa until they were forced to flee at Anschluss in March 1938, just ahead of the Gestapo squad sent to arrest them.

They were on the Gestapo hit-list because RCK and Hitler were political rivals. PanEuropa outsold Mein Kampf in the 1920s, so much so that in 1928 Hitler’s publisher declined to print a third volume while he still had such large unsold stock on his hands. In that third volume Hitler condemned RCK as “a cosmopolitan bastard”, dedicating several pages to an attack on PanEuropa as a rival to National Socialism. Hitler clearly wanted a German Europe and never forgave RCK for promoting the idea of a European Germany. For RCK, no one nation – neither a victor like France nor a defeated nation like Germany – could or should dominate the continent. A peaceful Europe required the consent of all European states and he organised chapters of PanEuropa in dozens of capitals across the continent to promote that vision.

Two years after RCK fled to Switzerland, where he still felt at risk, he dramatically escaped again, in June 1940, from Geneva across France and Spain to Lisbon. From here the Americans spirited him and his family to New York for the duration of the war, where he helped strengthen US support for Britain and later advised the US Administration develop plans for an integrated Europe after 1945.

But RCK’s politics seriously divided him from his elder brother, Johannes, who inherited the Ronsperg estate. Despite marrying a Hungarian woman who was half-Jewish, Johannes joined the Nazis and supported Henlein’s Sudeten German movement. He socialised with Nazi leaders in Berlin, offering lavish parties during the war. But as the war was ending he fell back on Ronsperg where he was interned by the Czechs in April 1945.

RCK did not learn of this in New York until December that year, but for him blood proved thicker than water. He cabled Benes, Fierlinger and Jan Masaryk – all of whom he knew personally – to ask them to intercede and have his bother released. But the charges were too serious and RCK was invited to correspond instead with a Czech lawyer appointed for Johannes’ defence. Only the transfer of the case from the revolutionary court to a new regional court saved him from the death penalty. Johannes was eventually expelled into the American zone of Germany and his property seized by the state. His estranged wife returned from wartime hiding in Switzerland to live with him for a while in Regensburg, where he died in 1961. He never spoke to RCK after his release and expulsion, believing that RCK had tried to have him expelled in order to ‘inherit’ the estate himself.

A younger brother, Gerolf, also had serious difficulties in 1945. After the German annexation he served in Prague as a press attaché in the Reichsprotektorat and later in the Wehrmacht as an interpreter in Brussels and on the staff of General von Kleist on the Eastern front. But a broadcast to Europe by RCK from New York in 1944 attacked Hitler personally and led in retaliation to an edict by the Führer that all members of the Coudenhove family should be dismissed from the Wehrmacht and the Nazi Party. This meant that Gerolf, once he returned to Prague, was not employed in the government but had to earn his living in the private sector and academia. As German authority collapsed in May 1945, he was interrogated by Czech police, and this ‘retaliatory’ edict must have stood him in good stead. He was allowed to join the last retreating column of Germans from the city, along with his wife and young children. They surrendered to the Americans several days later.

Churchill’s Zurich speech of September 1946 mentions the contribution of RCK and of PanEuropa towards the idea of the United States of Europe.

RCK returned to Europe from the USA and was instrumental in advising Churchill, de Gaulle and Adenauer in the turbulent years of post-war reconstruction. Churchill’s Zurich speech of September 1946 mentions the contribution of RCK and of PanEuropa towards the idea of the United States of Europe. In 1947 RCK set up the European Parliamentary Union with Europe-minded MPs in every democratic parliament of the continent. They lobbied for a constituent assembly that might deliver a truly United States of Europe after this second European civil war in a century. In 1948 he spoke immediately after Churchill at the opening of the great Congress of Europe in The Hague. He was guest of honour at the opening of the Council of Europe in 1949. In 1950 he was the first recipient of the Charlemagne Prize for services to European unity.

But with the Schuman Declaration in May that same year Jean Monnet set in train the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community. That introduced the ‘Community method’ of building political union by small steps that first created common interests among the member states. RCK realised this process of piecemeal economic cooperation could take forever and still not reach the finality of political union. He wanted a grand gesture, a leap of faith, the union of states that he had dreamed of back in the 1920s and worked for throughout his life.

When he died in July 1972, the United Kingdom had just agreed to join the European Community, a step in the right direction as far as he was concerned, but still not enough. Now with Brexit the UK has just left and – ironically – triggered a move towards deeper unity among the remaining states. Faced with contemporary problems as serious as climate change, migration, Russian belligerence on its borders and geopolitical rivalry between China and the USA, Europe may now realise it must – as he once wrote – ‘Unite or Perish’.

Are the challenges Europe faces today great enough to drive it to a more complete union? That would be what RCK would hope for. The drive towards a United States of Europe began as an attempt to stop border conflicts between them after the First World War. It moved to the Monnet vision of small steps after the Second. Is it now moving to a different plane today in a changed geopolitical situation?

This article was written before the Russian invasion of Ukraine.